Crisis in Eastern Europe: Putin’s Creation and Lukashenko’s Contribution

Increasingly shrill rhetoric, thousands of desperate people stuck without shelter in wintry conditions, and multiple dead amidst an escalating geopolitical stand-off at the Polish-Belarusian border. This is what it looks like when Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko follows through on his threat to “flood the European Union with migrants” in retaliation for EU sanctions. Naturally, when it comes to weakening the EU, Russian President Putin has been more than willing to lend a helping hand, by offering the regime in Minsk rhetorical backing, logistical support and military shows of force at the Polish-Belarusian border. However, the Kremlin might have set its sight on something higher than merely embarrassing the EU. Fears are growing, that while the world’s attention is fixed on the border between Poland and Belarus, Russia could go to war in Ukraine.

The Weaponization of Misery: Lukashenko’s contribution

Ever since the collective European trauma of the 2015 refugee crisis, threatening a massive influx of migrants has become an increasingly common tactic to extort the EU for money or other concessions. Turkey, Morocco, and several other countries have all engaged in it. What makes this time different is that instead of just not stopping already occurring migrant flows, the Belarusian regime was actively flying in would-be asylum seekers on additional air routes to pressure the EU. “Travel packages” for Middle Eastern migrants which include visa, flights, temporary accommodation and the cost of overland smuggle can cost up to €15,000. By all accounts a profitable business venture for the cash-strapped Belarusian state which has been under painful EU sanctions since the brutal repression of mass protests, and the mid-flight hijacking of a passenger jet in May 2021.

Accordingly, Lukashenko’s calculus was as cynical as it was transparent: Offer the EU to resolve this crisis of his own making in return for the lifting of sanctions and monetary rewards. However, the ploy backfired. Instead of meekly playing along, Poland sealed its border while the EU successfully stopped migrant flights at their source and moved to broaden sanctions against the regime. Thereby, leaving the Belarusian strongman stuck with thousands of stranded migrants in rapidly deteriorating weather conditions.

Belarus in the Russian Bear Hug

Although it is unclear if this crisis at the Polish-Belarusian border was truly “masterminded in Moscow” as the Polish prime minister has alleged, Putin is clearly one of its main beneficiaries. The more painful the sanctions of the West, the more dependent Lukashenko becomes on Russia. It is no coincidence, that after years of dragging its feet the Belarusian regime saw itself forced to sign up to closer politico-economic integration with Putin’s Russia. In the end, this so-called “union state” is supposed to entail the creation of supranational governing bodies, a single currency, and a common defence policy. Previously, the Belarusian dictator was often able to play Russia and the West off against each other to protect his position. However, Lukashenko’s growing isolation abroad and unpopularity at home are rapidly diminishing his negotiation leverage, which among other things has resulted in a growing Russian military presence in Belarus.

Ukraine: The Next Victim?

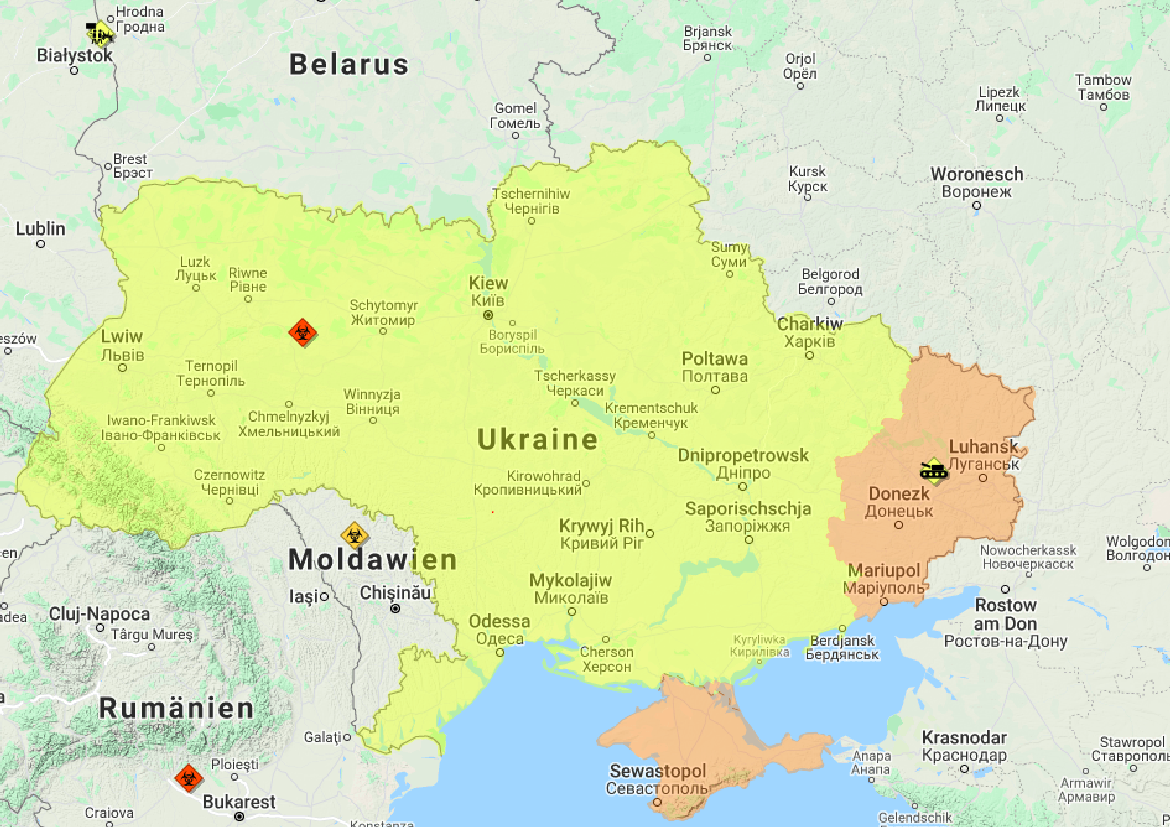

It is not just Belarus’ western neighbours that are worried about the growing proximity between Moscow and Minsk, the Ukrainian government also fears that it might be next on the target list. Therefore, Ukraine has deployed 8,500 additional security forces to its border with Belarus. Yet, it is not primarily migrants that are causing alarm in Kiev, but more the about 100,000 Russian military forces that have recently been positioned around Ukraine. Likewise, Lukashenko has apparently also moved significant military forces to the border with Ukraine and pledged his support to Russia in case of conflict, while, US intelligence services, warn of the “high probability of Russian military escalation” in the coming months.

It seems almost cynical to speak of a possible Russian attack on Ukraine, considering that Putin has arguably never stopped assaulting the country. The military seizure of the Crimean peninsula in 2014, was immediately followed by the instigation of a proxy war in eastern Ukraine that continues to this day and has killed more than 14,000 people. So what does the Russian military build-up mean for Ukraine? From a full-scale invasion, expansion of support to pro-Russian separatists, energy blackmail, or merely another round of sabre-rattling and grandstanding everything is on the table. Moscow’s furious denials combined with ominous warnings about “increasing provocations” directed against Russia have done little to allay fears of escalation. Although, experts believe the military build-up to be qualitatively different from previous such occasions, a limited attempt to destabilize Ukraine currently appears to be the most likely scenario – if no one miscalculates that is.

Since the what appears elusive, the question of why might be easier to answer. First, those most likely to oppose aggressive action against Ukraine are all either distracted and or are constrained in their capacity to act. In the United States, the heated feuding over domestic issues and a shifted foreign policy focus towards the Indo-Pacific have cast doubt on how far the Biden administration would go to push back against a Russian incursion. Likewise, surging COVID-19 numbers in Europe, the formation of a new government in Germany and an upcoming presidential election in France are all drawing attention inwards. Additionally, skyrocketing energy prices throughout Europe severely limit the EU’s room for manoeuvre when it comes to taking action against one of its major energy suppliers.

Conversely, the Russian population could do with some distraction themselves, considering that even according to the dubious official numbers Russia suffers from one of the highest COVID-19 related death rates in the entirety of Europe. Moreover, in 2014, the annexation of Crimea led to a major boost for Putin’s approval ratings and a repeat performance might be looking rather tempting right about now. Consequently, we could soon witness Putin’s personal take on the age-old saying: Never let a good crisis go to waste – particularly if you are the one creating it.

The situation remains volatile and could escalate quickly and with little warning. Travellers in Eastern Europe should therefore follow A3M coverage of events at the Polish-Belarusian border as well as in Ukraine closely. See here for coverage of the border crisis and here for potential developments in Ukraine.