Quo Vadis Ethiopia: Two Wars for the Price of One?

by Michael Trinkwalder

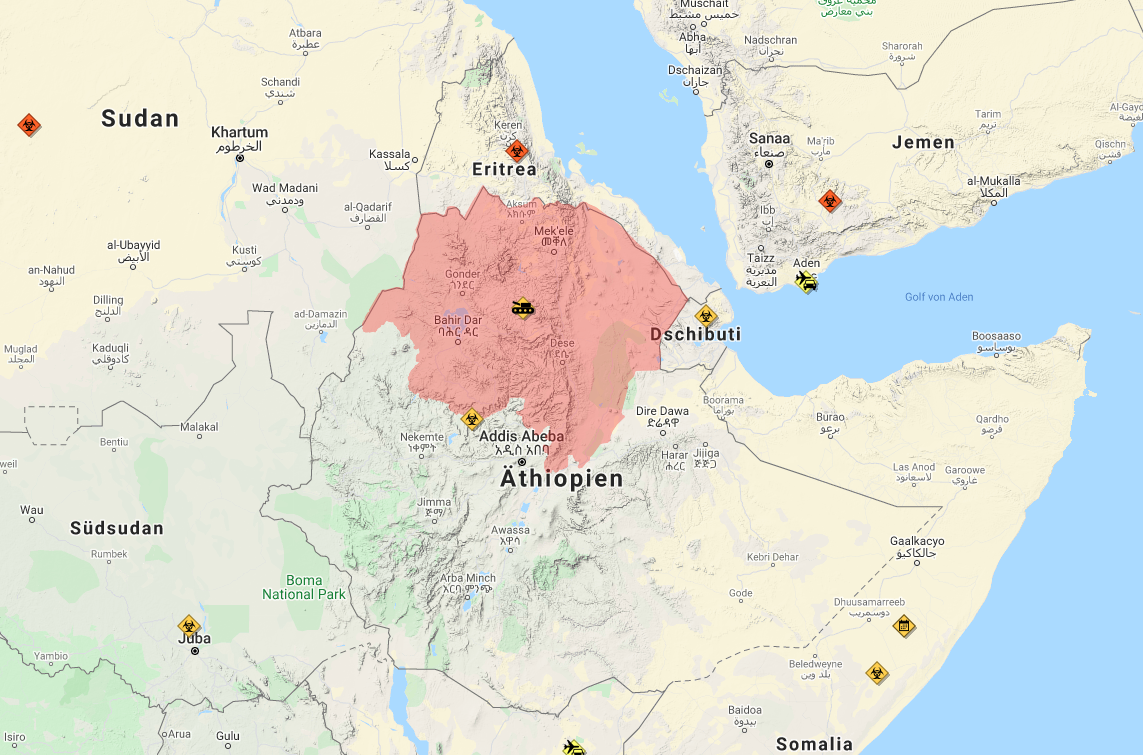

Perhaps it is time to only award the Nobel Peace Prize after political retirement. Similar thoughts might have gone through the heads of the Nobel Committee when Nobel Peace Prize winner and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali triggered a civil war in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in November 2020. What was supposed to be nothing more than “a large-scale law enforcement operation” with “limited and achievable” objectives, turned into a protracted armed struggle that in light of recent developments the Ethiopian Armed Forces might very well lose. However, just as the civil war continues to escalate, Ethiopia is also facing down the threat of a full-scale inter-state war on the Horn of Africa.

An Auspicious Beginning

When Abiy Ahmed Ali came to power in April 2018, a flurry of highly ambitious reforms quickly made him the darling of international media: Among other things, he ended the country’s two-year-long state of emergency, released thousands of political prisoners, reached out to the opposition, lifted restrictions on the media and promised to significantly liberalize the economy as well as the political system. If anything, Abiy’s foreign policy agenda was even more ambitious, with him setting out to bring to an end the nearly 20-year cold war between Ethiopia and its northern neighbour Eritrea. Yet in spite of this highly ambitious goal, in record time an agreement was reached to re-establish diplomatic relations and re-open borders. It was this remarkable achievement that won him the Nobel peace Prize in 2019. In sum, his seemingly progressive vision and youthful energy made him an ideal projection surface for those hoping that he would turn his ethnically diverse country into a role-model to the rest of the continent. However, not all were happy with the rapid pace or even the direction of the reforms.

War in Tigray: Nobel Peace Prize Winner Going Rogue?

Foremost among these opponents was the Tigray’s People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the ethnic-based party that prior to Abiy’s rise to power had dominated the Ethiopian government for almost three decades. Tensions came to a head in September 2020 when the TPLF went ahead with regional elections in Tigray, despite a federal order to delay all elections due to the pandemic. Relations continued to deteriorate and finally, in early November the TPLF launched what it claimed to be pre-emptive attacks against federal positions in Tigray. In response, the Ethiopian government launched a major military intervention involving tens of thousands of regular soldiers supported by large numbers of paramilitary forces from the Amhara region and surprisingly also the country’s former arch-enemy – the Eritrean military.

With the weight of numbers on its side and facing a divided opposition, the Ethiopian military made quick progress. Within a month, most of the Tigray region had been captured, including its capital Mekelle. Despite the relative brevity of the fighting, the results were devastating; thousands were killed, millions were displaced and hundreds of thousands were thrown into famine conditions. What followed may well have been worse, with reports emerging of widespread indiscriminate killings and starvation of civilians, mass-scale sexual violence, ethnic cleansings, with the worst offenders being Eritrean forces taking revenge for past grievances. Thereby, uniting the population against the occupation and driving thousands of highly motivated new recruits into the ranks of the TPLF rebels.

Reversal of Fortunes

In late June 2021, just as Abiy was coasting to an overwhelming election victory in the rest of the country, the newly rebranded Tigray Defence Forces (TDF) launched a devastating counter-attack that saw Ethiopian military positions in the region “fall like dominoes.” Within days, Ethiopian forces were forced to make a hasty retreat first from the regional capital and subsequently from much of the Tigray region. The TDF claims to have either captured or killed tens of thousands of Ethiopian soldiers. While this is difficult to verify, there can be no doubt that losses were heavy. In the aftermath of this debacle, Prime Minister Abiy declared a unilateral “humanitarian ceasefire,” but this was immediately rejected by the TDF who vowed to fight until “every inch of Tigray was liberated.” Worryingly, the conflict is not just escalating but is also becoming increasingly dominated by the question of ethnicity – which does not bode well for the future of the multi-ethnic Ethiopia.

Already, fighting is taking place outside of Tigray and previously uninvolved Ethiopian ethnic groups are sending military reinforcements, further fuelling ethnic nationalism in the country. Only one thing seems certain, the civil war in Ethiopia will most likely not end any time soon. When Ethiopian forces had to retreat from Mekelle, government officials in Addis Ababa initially claimed this to be merely a tactical decision, made necessary by the need to confront outside threats. What may have been no more than a transparent attempt to save face, could prove to be prophetic.

Water War: Dammed if You Do, Damned if You Don’t

After all, its protracted civil war makes Ethiopia appear weak. Already, Sudan exploited the Ethiopian predicament to seize control of the disputed highly fertile al-Fashaga region. Yet, it is not land disputes, but the contested waters of the Nile that pose the most danger of causing a full-scale inter-state war. The flashpoint is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) that Ethiopia has been building on the Blue Nile River right next to the border with Sudan since 2011. Once fully operational, the dam would roughly double the electricity output of the chronically energy-poor Ethiopia, thereby providing a major boost to the economic growth of Africa’s second-most populous country. However, the Nile also supplies Egypt with over 97% of its drinking water and is also immensely important for Sudan. Therefore, the completion of the dam would effectively put the two countries at Ethiopia’s mercy.

Unsurprisingly, both Egypt and Sudan are vociferously opposed to the GERD project and point to colonial-era agreements that allocate the overwhelming majority of the Nile’s water to the two countries and which Ethiopia does not recognize. Egypt’s President el-Sisi has threatened that “all options are on the table” and has concluded a military cooperation agreement with Sudan, which also sees its national security threatened by the GERD. That their fears are not entirely unfounded was underlined when Ethiopia closed the dam gates with no advance warning in July 2020. As a consequence, water levels on the Nile plummeted dramatically, which left millions of people in Sudan’s capital without a steady supply of drinking water for days and also brought the agricultural irrigation systems along the Nile to a standstill.

Egypt and Sudan are insisting on a binding agreement regulating the operation of the GERD, but Ethiopia has stubbornly refused to budge while continuing to fill the dam. Neither of the principal actors in the dispute can easily back down since both Cairo as well as Addis Ababa consider the GERD issue to be of existential importance. With negotiations deadlocked and in light of Ethiopia’s current military weakness as well as diplomatic isolation, a military solution to the GERD conundrum might become exceedingly tempting for Egypt. Consequently, as little as a regional drought could set off the 21st century’s first water war.

Quo Vadis Ethiopia?

His overwhelming election victory notwithstanding, Prime Minister Abiy is in an unenviable position. He has lost considerable standing at home as well as abroad. Already struggling with an escalating civil war, increasing ethnic tensions and a lacklustre economic performance another war is the very last thing Abiy and Ethiopia need. At the same time, the Ethiopian Prime Minister can ill afford yet another setback, which is unlikely to make him any more willing to compromising. If the crises keep piling on, this might very well mean the end. Not just of his government or reform agenda, but possibly also of Ethiopia.